Inadequate wound assessment can lead to inappropriate wound management, leading to lack of healing, increasing costs in nursing time, use of unnecessary and/or inappropriate products, and a decrease in patient quality of life.[1]

In order to make the most of wound assessment, it should be incorporated as a holistic and ongoing part of wound management.

Comprehensive wound assessment — and regular reassessment — are the tools that guide care so the wound can achieve closure and healing in the most clinically efficient and resource-effective way possible.

Setting management goals

Wound healing is a complex and multifaceted process influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic factors, some of which can be controlled.[2]

To get a handle on these factors and delineate which can be controlled through wound management or concomitant management for other conditions, baseline data should be recorded when the patient presents with the wound.

This allows the clinician — or a new clinician — to quantitatively and qualitatively measure progress, deterioration or stagnation in the wound status going forward.

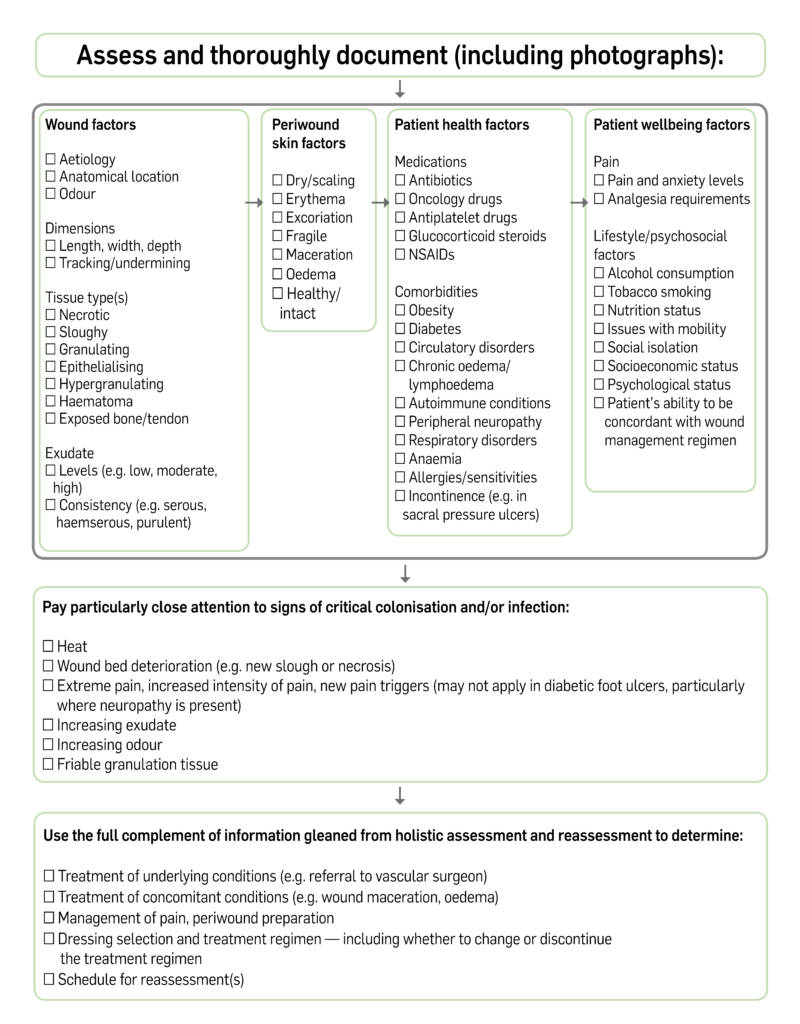

As such, baseline assessment should encompass a number of factors:

With this information recorded, the clinician can paint the full picture of the wound and set management goals, including:[3]

- moisture balance correction or maintenance

- appropriate debridement and preparation of the wound bed and periwound skin

- reduction of the microbial load

- referral for management of comorbid (e.g. incontinence, obesity) or underlying (e.g. vascular insufficiency, diabetes) conditions

- expected appropriate healing trajectory

- potential dressing or wound management product options that may be appropriate initially or on an ongoing basis (e.g. honey dressings should be used with caution in people with diabetes, silver-containing dressings should be time-limited)

- schedule for reassessment

Where a patient has more than one wound, each one should be assessed separately and have a separate, documented plan for management.[4]

High-risk factors and influence on reassessment

All wounds will have a degree of colonisation and must be controlled for over the course of management.[5]

If critical colonisation or infection is suspected at initial presentation, the use of appropriate antimicrobial wound management products should be included in the treatment goals.[4]

If the wound is not clinically judged to be critically colonised/locally infected at presentation, it is still of the utmost importance to be on the lookout for factors that might indicate the patient is at a high risk for infection or stalled healing due to other causes:[2,6–9]

- Size: New wounds that are large in size or depth may be more difficult to bring to closure.

- Wound location: Anatomy that traps moisture may lead to skin breakdown, and dressings may be more difficult to apply securely in some locations.

- Vascular compromise: Inadequate vascularisation has a deleterious effect on wound healing, and must be treated, often by a specialist.

- Excessive exudate: Some exudate is normal, but too much can break down skin and stop the formation of new, healthy tissue in the wound bed.

- Excessive inflammation: Some degree of inflammation is required during the proliferative phase and, indeed, inflammation may increase when healing is restarted in a stalled wound. However, excessive inflammation may be a sign that a wound will fail to heal along the expected trajectory.

- Diabetes: Not only does the underlying disease impede healing, neuropathy that is often present can lead to further damage that patients don’t realise has occured; diabetes should be managed in coordination with the appropriate member of the multidisciplinary team.

- Obesity: This comorbidity is associated with increased risk of skin and wound infection, dehiscence, haematoma and seroma formation, and creates physiological stresses that may delay wound healing.

- Immunocompromise: Impaired immune system activity is deleterious to the healing process in general, and makes these patients more likely to develop wound infection and its associated complications.

- Medications: Some drugs, such as those for cancer, glucocorticosteroids and some cardiovascular therapies, can impede healing.

- Nutritional status: Deficiencies in nutrition make healing more difficult.

- Substance use: Smoking tobacco and consuming alcohol are associated with a decreased ability to heal.

- Compromised mobility: Extended periods of sitting and lying down puts pressure on wounds that can lead to breakdown, and lack of activity can make management of underlying conditions (e.g. vascular compromise, obesity, diabetes) more difficult.

- Age: Very young and elderly patients inherently have age-related impairment of macrophage function, present with physiological differences that may complicate wound healing, and are at greater risk of wound infections.

Wounds that are at an elevated risk for stalled healing should be subject to more frequent reassessment — for example, twice a week instead of once weekly — depending on your local care guidelines.

Reassessment is critical for tracking all aspects of the wound and patient status.

As such, any wound should be regularly reassessed, in order to look for signs that the chosen wound management approach is not working, or that wound healing may become stalled.

For example, expanding size/depth, increases in exudate and/or slough, increasing excessive inflammation, and deterioration in the observable ‘health’ of the wound bed or wound edge tissue may all be signs that healing will be delayed, or that a change in topical wound agent is needed.

Once a wound stalls, restarting healing can be a difficult task, and so it is critical in terms of time, resources and patient well-being to stay on top of the wound status.

Educating patients is key

Careful assessment, re-assessment and documentation should highlight the factors that require consideration by the entire multidisciplinary team involved in a patient’s care — and that includes the patient.

It is therefore important to assess the patient’s knowledge and understanding of their wound and general condition, and to provide them with clear education around ongoing care, their involvement and follow-up arrangements.

Information provided to patients should include signs or symptoms that would trigger the need to be seen by a clinician outside the follow-up schedule, and whom they should contact.

After all, patients are able to ‘reassess’ their wounds on a daily basis, and can be the multidisciplinary team’s eyes on the ground.

The importance of the patient to comprehensive wound assessment and the functioning of the care team should not be underestimated.

References

- Wounds International International Consensus: Optimising wellbeing in people living with a wound. London, UK: 2012.

- Wounds UK Best Practice Statement. The use of topical antimicrobial agents in wound management. London, UK: 2013.

- Conforth A. Holistic assessment: the patient and wound. Independent Nurs, 21 October 2013. Available at: http://www.independentnurse.co.uk/clinical-article/holistic-assessment-the-patient-and-wound/63468/

- NHS Quality Improvement Scotland. Paediatric assessment chart for wound management. 2009. Available at: http://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/our_work/patient_safety/tissue_viability_resources/paediatric_wound_chart.aspx

- Wounds UK Best Practice Statement. Principles of wound management in paediatric patients. London, UK: 2014.

- Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res 2010;89(3):219-29

- Hess T. Checklist of factors affecting wound healing. Adv Skin Wound Care 2011;24(4):192

- Vowden P. Hard-to-heal wounds Made Easy. Wounds Int 2011;2(4).

- Cutting K, Vowden P, Wiegand C. Wound inflammation and the role of a multifunctional polymeric dressing. Wounds Int 2015;6(2):41–6