The importance of macrophages in wound healing and cellular debridement

Most people are not exactly fans of housekeeping, the chores often pile up to a point where even the thought of getting started wears you out – sounds familiar?

Well the importance of good housekeeping can also apply to stalled and chronic wounds. It’s a well recognized fact that the majority of chronic wounds is stuck in the inflammatory phase [1], where an imbalance between different molecules contributes to the characteristics of a chronic wound such as:

- Persistent low-grade inflammation (i.e. a chronic inflammation cycle)

- Imbalance between matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors (MMP/TIMP)

- Lack of growth factor (GF) /destruction of GFs by MMPs

- Destruction of Extra Cellular Matrix (ECM)

- Senescent cells

These factors are all in part resulting from inappropriate housekeeping skills by macrophages.

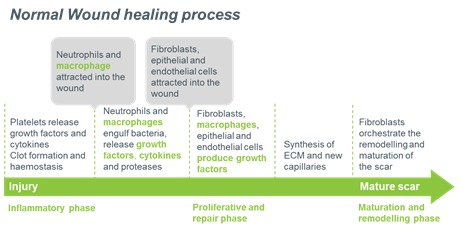

In normal wound healing, a large amount of inflammatory cells are attracted into the wound bed to combat potential pathogens that might have invaded through the broken skin and to remove damaged tissue. These cells are short lived and need to be cleared in order for the wound healing process to progress to the next stages of healing [3]. This task is performed by macrophages through a process called phagocytosis (the dead cells are engulfed by the macrophages). The phagocytosis of dead cells by the macrophages is a powerful signal for the macrophages to resolve the inflammatory response[3]. This is achieved by release of molecules (cytokines) from the macrophages. These molecules signal to the other cell types to end the inflammatory phase and move onto the next phase of healing, namely the proliferative stage (Figure 1).

Elderly and diabetics have altered macrophage functions and often show delayed wound healing capacity

The problems with stalled wound healing and chronic wound conditions usually arise in elderly patients and diabetics.For these patients it is demonstrated that the macrophages have altered functions[2] and often also show senescent qualities (premature aging). For this group of wound patients, the macrophages are exhausted before they can finish the job of phagocytosing the dead cell corpses of the inflammatory response. This results in a pile up of cell corpses from the inflammatory phase (not unlike the laundry basket of the author). Thus, the signal to move onto the next phases of healing are not provided and the viscous circle of low-grade inflammation of a chronic wound starts with the characteristics listed above.

Ending the inflammation circle in stalled and chronic wounds by reactivation of the macrophages

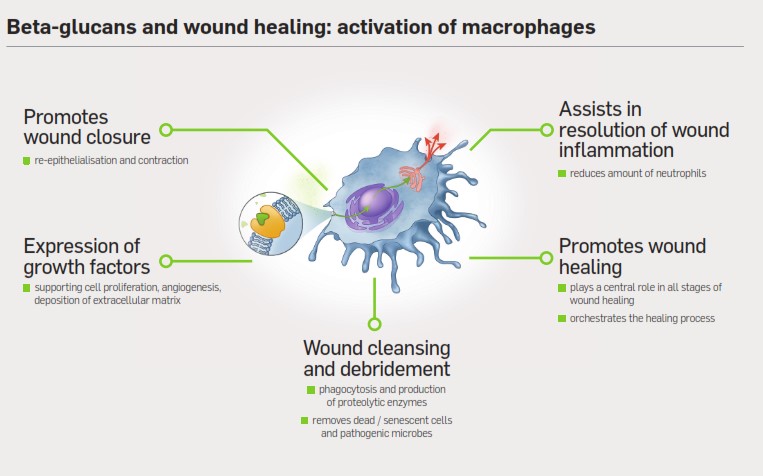

So for stalled wound conditions targeting the macrophages to restore their normal functions both as “housekeepers” and as a coordinator for the normal healing process, is an intriguing idea[4].

The good news is that macrophages from elderly and diabetics are responsive to stimulation by some compounds which can restore most of their functions [5]. One such compound is soluble beta-glucan (SBG), which is a component of the topical wound gel Woulgan. By applying SBG to a stalled wound, macrophages are reactivated and become trained “housekeepers” and coordinators of the healing process. From a practical point of view in the management of stalled wounds, this means that you don’t need to know exactly what’s going on at the molecular level, or which factors are out of balance. You can simply target the macrophages and train them by applying Woulgan to reactivate the whole healing process.

References

- Chen, W.Y.J. and A.A. Rogers, Recent insights into the causes of chronic leg ulceration in venous diseases and implications on other types of chronic wounds. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 2007. 15(4): p. 434-449.

- Jason Maggi, Madhu Ragupathi, Marjana Tomic-Canic, Harold Brem; Chronic Wounds, Age and Impared Healing Potential. Advances in Wound Care 2010;Volume 1; 177-182

- Sashwati Roy; Inflammation, Resolution of Inflammation in Wound Healing: Significance of Dead Cell Clearance. Advances in Wound Care 2010;Volume 1; 253-258

- Robert J. Snyder; John Lantis; Robert S. Kirsner; Vivek Shah; Michael Molyneaux; Marissa J. Carter; Machrophages: A review of their role in wound healing and their therapeutic use. Wound Repair and Regeneration 2016; 24; 613-629

- Sashwati Roy PhD,Ryan Dickerson BS, Savita Khanna PhD, Eric Collard BS, Urmila Gnyawali RN,Gayle M. Gordillo MD, Chandan K. Sen PhD; Particulate β-glucan induces TNF-α production in wound macrophages via a redox-sensitive NF-κβ-dependent pathway. Wound Repair and Regeneration 2011 Volume 19, Issue 3; 411–419