At any point in the healing trajectory, a wound can become stalled.

That is, the wound initially began to heal, but patient- or wound-related factors have prevented the wound from continuing to heal in an orderly and timely manner.

The wound is stuck — ‘stalled’ — in the inflammatory phase, as indicated by a lack of healing progress.[1,2]

It has been documented that a diabetic foot ulcer presenting with less than 40% size reduction in 4 weeks has a 91% risk of not healing in 12 weeks.[1]

In addition, an evidence-based algorithm for venous leg ulcer care suggests that less than 40% healing in 4 weeks indicates a heightened risk of non-healing with standard care.[2]

This stalling can occur spontaneously and unexpectedly, even with a well-thought-out healing plan based on thorough assessment in place.

When wounds are challenging and healing has stalled, the experience can be frustrating for clinicians and patients alike.

Clinicians may express resignation, and patients may become hopeless or even experience more severe psychological and emotional consequences.

Sometimes, simply changing the dressing routine or introducing new elements to the wound management regimen may be enough to kickstart a new wound healing process.

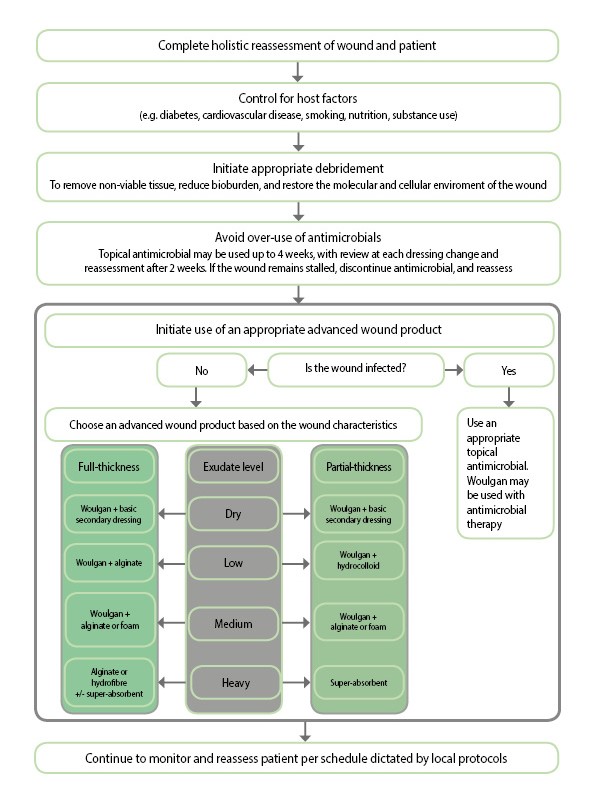

However, in order to prevent a stalled wound from becoming chronic, advanced management may be required to restart healing and/or achieve closure (see figure).[3]

1. Use appropriate debridement

The presence of non-viable tissue and slough produces an abnormal wound environment that may interfere with wound healing.

To restart healing in stalled wounds, the molecular and cellular environment of the wound must resemble that of a healing acute wound.[4]

Debridement helps to achieve this by removing the factors that contribute to a wound environment that is more likely to support a heavier microbial burden.

Reducing the bioburden and the presence of biofilms within the wound further decreases the proinflammatory responses, leaving the body more able to form granulation tissue in the wound bed.[5]

Wounds may require repeated, or ‘maintenance’, debridement to keep them from re-stalling.[6]

Debridement should be driven by clinical need — it should be considered an integral part of stalled wound management and not merely an ‘add-on’ — and the method chosen should account for relevant factors:[7]

- Wound- and debridement-related pain levels reported by the patient

- Skill level of the clinician (with referral to another member of the multidisciplinary team, if necessary)

- Amount and type of non-viable tissue to be removed

- Anatomical location of the wound.

Considering these factors will help determine the method of debridement that is most effective for the patient.

2. Avoid over-use of antimicrobials

In discussion with clinicians, it sometimes becomes apparent that many have tried just two different approaches and repeated these approaches in an alternating fashion over weeks and months, even years.

Typically in these instances, a treatment plan based on the initial assessment has been implemented, using basic/standard dressings such as hydrogels, foams or hydrofibers.

When improvement fails to occur, a switch to an antimicrobial product is common, often for extensive periods of time and sometimes even without confirming an infection or a critically colonized wound.

However, although topical antimicrobials present limited potential for systemic absorption and toxicity, they should be used only when signs and symptoms suggest that wound bioburden is interfering with healing, or when there is an increased risk of infection.[8]

Clinical colonisation must be determined in the context of all information about the wound and patient, and selection of an antimicrobial product should occur according to the specific needs of each wound and patient, weighing the advantages and drawbacks of use.[8]

Once started, the effect of the antimicrobial on the wound must be closely monitored, with review at each dressing change and reassessment after 2 weeks.

If there are signs of healing progression, and a reduction in the signs and symptoms of infection or critical colonisation, the antimicrobial dressing should be discontinued.

If the wound has not progressed, the antimicrobial may be continued for 2 more weeks.

However, if the wound remains stalled after 4 weeks of antimicrobial use, the topical antimicrobial should be discontinued, and the patient and wound fully reassessed.

Using topical antimicrobials does not guarantee a healing outcome.

Used in a cycle with standard dressings meant to provide optimal moist wound-healing conditions, the body is left to fix the wound on its own, when the patient and wound may in fact require an extra ‘push’ to restart the healing process.

3. Implement advanced wound management

When wounds fail to achieve sufficient healing after 4 weeks of standard care or after 4 weeks of treatment with a topical antimicrobial product, reassessment of underlying pathology and consideration of the need for advanced therapeutic agents should be undertaken.[9]

Changing from one foam to another is usually not enough to reactivate a stalled wound, so a more active product needs to be chosen.

With so many products available, it’s no wonder clinicians sometimes get lost.

The factors that cause wounds to stall — and cause frustration for clinicians and patients — are many, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

However, progress has been made in both the knowledge of how to treat stalled wounds and in the availability of active therapies, and there may be space for clinicians to try an active product that upends the ‘same old’ (see figure).[10]

Selection of an appropriate therapy should be evidence-based,[9] while also recognising that the healing of stalled wounds may require an active therapy that helps restore optimal healing conditions in the wound bed as well as kickstarting the patient’s own ability to heal.

Conclusion

If the wound is stalled, practice should not be similarly stalled.

To restart healing in stalled wounds, it is important to address factors that affect the wound environment — i.e., patient and wound history, bacteria, and nonviable skin, as well as moisture (often a factor of dressing characteristics).

Sustaining the appropriate environment, along with the use of an active healing product such as Woulgan, will support progression of the wound to closure.

References

- Sheehan P, Jones P, Giurini JM, et al. Percent changes in wound area of diabetic foot ulcers over a 4 week period is a robust predictor of complete healing in 12 week prospective trial. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117(7 suppl):239S–244S

- Kimmel HM, Robin AL. An evidence-based algorithm for treating venous leg ulcers utilizing the cochrane database of systematic reviews. Wounds 2013;25(9):242–50

- Raffetto JD. The definition of the venous ulcer. J Vasc Surg 2010;52(5 Suppl):46S–49S

- Schultz GS, Sibbald RD, Falanga V, et al. Wound bed preparation: a systematic approach to wound management. Wound Repair Regen 2003;11:S1-28.

- Wolcott RD, Kennedy JP, Dowd SE. Regular debridement is the main tool for maintaining a healthy wound bed in most chronic wounds. J Wound Care 2009;18(2):54-6.

- European Wound Management Association (EWMA). Position Document. Wound bed preparation in practice. MEP Ltd: London, 2004.

- Gray D, Acton C, Chadwick P, et al. Consensus guidance for the use of debridement techniques in the UK. Wounds UK 2011;7(1):77-84.

- Wounds UK Best Practice Statement. The use of topical antimicrobial agents in wound management, third edition. London: Wounds UK, 2013.

- Frykberg RG, Banks J. Challenges in the treatment of chronic wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015;4(9):560-82

- Glover D. The wound dressing maze: selection made easy. Dermatol Nurs 2013;12(4):29-34.